En viitsi osallistua tähän kinasteluun, mutta jumaloitumisesta tämän verran:

Serafim Seppälä artikkelissa Jumalallistuminen – mikä on kysymys? teoksessa Jumalan kaltaisuuteen. Aatehistoriallisia tutkielmia elämän päämäärästä s. 100: [Pseudo-]Dionysioksen määritelmän mukaan theosis on ”Jumalan kaltaisuuden ja hänen kanssaan yhdistymisen saavuttamista siinä määrin kuin mahdollista”. Serafim Seppälä: ”Määritelmän nerokkuus on sen suhteellisuudessa: sen voi tulkita minimalistisemmin tai maksimalistisemmin.”

Filokalia 3 (käsitteiden selityksistä) s. 358–359: Jumalallistuminen, jumaloituminen (theosis). Pyhien isien opetuksen mukaan ihmisen päämääränä on jumalallistuminen eli, heidän omaa rohkeaa ilmaisuaan käyttääksemme, tuleminen jumalaksi. Tällä ei suinkaan tarkoiteta, että ihmisestä pitäisi tulla jokin itsenäinen palvottava jumaluus, vaan että hänen tulee saavuttaa Jumalan kaltaisuus. Armon kautta hänestä tulee sellainen, jollainen Jumala on luonnostaan. Hän on asemansa puolesta jumala – ei luontonsa puolesta. Tämä taas on mahdollista ainoastaan osallisuuden kautta Jumalaan.

The Orthodox Study Bible p. 1692:

Deification is the ancient theological word used to describe the process by which a Christian becomes more like God. St. Peter speaks of this process when he writes, “As His divine power has given to us all things that pertain to life and godliness … you may be partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pt 1:4).

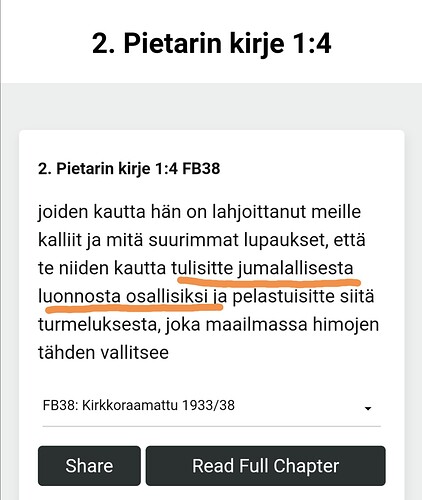

- Piet. 1:4 Näin hän on meille lahjoittanut suuret ja kalliit lupaukset, jotta te niiden avulla pääsisitte pakoon turmelusta, joka maailmassa himojen tähden vallitsee, ja tulisitte osallisiksi jumalallisesta luonnosta. – –

What deification is not. When the Church calls us to pursue godliness, to be more like God, this does not mean that human beings become divine. We do not become like God in His nature. That would not only be heresy; it would be impossible. For we are human, always have been human, and always will be human. We cannot take on the nature of God. – –

In John 10:34, Jesus, quoting Psalm 82:6, repeats the passage, “You are gods.” – – Jesus is not using “god” to refer to divine nature. We are gods in that we bear His image, not His nature.

What deification is. Deification means we are to become more like God through His grace or divine energies. In creation, human were made in the image and likeness of God according to human nature. In other words, humanity by nature is an icon or image of deity. The divine image is in all humanity. Through sin, however, this image and likeness of God was marred, and we fell.

When the Son of God assumed our humanity in the womb of the blessed Virgin Mary, the process of our being renewed in God’s image and likeness was begun. Thus, those who are joined to Christ, through faith, in Holy Baptism begin a process of re-creation, being renewed in God’s image and likeness. We become, as St. Peter writes, “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pt 1:4).

Because of the Incarnation of the Son of God, because the fullness of God has inhabited human flesh, being joined to Christ means that it is again possible to experience deification, the fulfilment of our human destiny. That is, through union with Christ, we become by grace what God is by nature – we “become children of God” (Jn 1:12). His deity interpenetrates our humanity. – –

Nourished by the Body and Blood of Christ, we partake of the grace of God – His strength, His righteousness, His love – and are enabled to serve Him and glorify Him. Thus we, being human, are being deified.

Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, Orthodox Christianity Volume II Doctrine and Teaching of the Orthodox Church p. 372:

The theme of deification grows from the roots of the New Testament teaching that people are called to become ”partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet 1.4). At the foundation of the Greek fathers’ teaching on deification lie Christ’s words as well, by which he called people “gods” (Jn 10.34; Ps 82.6); also the words of John the Theologian on God’s adoption of people (Jn 1.12) and the divine image in man (1 Jn 3.2); many texts of the Apostle Paul, in which the biblical teaching on the image and likeness of God in man is examined (Rom 8.29; 1 Cor 15.49; 2 Cor 3.18; Col 3.10); the teaching of God’s adoption of people (Gal 3.26, 4.5); and the teaching on man as a divine temple (1 Cor 3.16). The eschalotogical vision of the Apostle Paul is characterized in terms of the exalted state of humanity after the resurrection, when mankind will be transfigured and raised up by its Head – Christ (Rom 8.18–23; Eph 1.10) and when God will be “all in all” (1 Cor 15.28). – –

The following phrases of Irenaeus lie at the basis of the teaching of deification:

“[The Word of God] did, through his transcendent love, become what we are, that he might bring us to be even what he is himself.”

“For it was for this end that the Word of God was made man, and he who was the Son of God became the Son of man, that man, having been taken into the Word, and receiving the adoption, might become the son of God.”

The claim that man becomes god through the incarnation of the Word of God is the cornerstone of the teaching on deification of the subsequent Fathers of the Church. – –

P. 373: The verb theopoieō (“to make like god”, “to deify”) is first found in Clement: “The Word deifies man by his heavenly teaching.” – –

Contained in Athanasius is the classic formula expressing the deification of man: “[The Word] became man that we may become God.” In another place Athanasius says of Christ: “For he has become man, that he might deify us in himself.” For Athanasius, as for the others fathers of the age of the ecumenical councils, the only basis of the deification of man is the incarnation of the Word of God. Athanasius emphasizes the ontological difference between, on the one hand, our adoption by God and deification and, on the other hand, the sonship and divinity of Christ: in the final deification “We too become sons, not as he in nature and truth, but according the the grace of thim that calleth.”